Biology and technology have a lot in common. Both involve a process of growth and change over generations. The smartwatch you wear today that can make phone calls, connect to the internet, take photographs, and more (in addition to telling the time, of course) has a couple of great great grandparents.

The Seiko Ruputer

On June 10, 1998, Seiko introduced the Ruputer, a wearable wrist device that has a credible claim as the world’s first smartwatch. Later called the OnHand PC, the Ruputer could connect to a PC and run applications using buttons around the screen in conjunction with an eight-way joystick below the screen. The joystick was necessary since 1998 was the “pre-touchscreen era.” You could

- play games

- set calendar appointments

- write memos

- create a to-do list

All of this right from your wrist. We wouldn’t give the Ruputer more than a nod today, but at the backend of the 20th century, it was a big deal.

The Ruputer had nowhere near the features and functions of today’s smartwatches, but if you were tech-savvy, you could get a few third-party apps like a version of Paint and a stick figure of the Kama Sutra to spice up your love life. And rather than a rechargeable cell, the Ruputer ran on two standard CR2025 watch batteries. By activating the power management system, it was possible to get a standby time of about three months. But any function beyond checking the time required you to swap out the batteries in as little as 30 hours.

Seiko Ruputer Specifications

Today, the smartwatch has evolved to use voice typing or connect to a smartphone to enter calendar appointments and the like. Still, that tiny screen was considered as cutting edge technology.

And the Ruputer featured:

- a 16-bit, 3.6 MHz processor,

- 128 KB of RAM

- 2 MB of non-volatile storage memory

- a 102×64 pixel monochrome LCD

- a serial interface

- an IR port to communicate with other devices

Those familiar enough with technology could use the included software to synchronize data to a PC. Programmers could create software in the C programming language.

Reviews of the Seiko Ruputer

Smartwatches often must be larger and chunkier to accommodate bigger batteries and more functions.

One reviewer posted in the Gadgeteer in January of 2000 that the Rupeter was “large and bulky on the wrist.” The watch had to be worn over the cuff rather than tucking nicely underneath.

Another reviewer in EW’s Gadget Zone berated the tiny size of the two-inch screen. They compared entering text to putting in your name as a high score on an arcade game with a joystick to “doing that with a single thumb.”

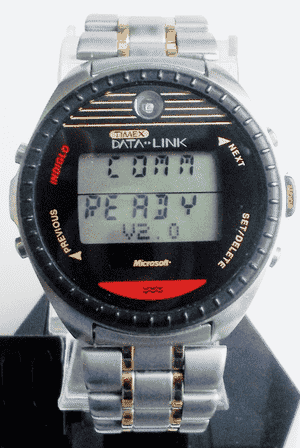

The Timex Datalink – Another Smartwatch Predecessor

If we think of the Seiko Ruputer as the “grandfather of the smartwatch,” we must consider the great grandfather. Further research reveals that the Timex Datalink, developed in conjunction with Microsoft, had its day in the limelight four years earlier in 1994. Capable of downloading information from a PC, log dates, and sending reminders and alerts, some technology gurus claim it to be the first smartwatch.

Early models included the Datalink 50, 70, and 150. The model numbers corresponded with the number of contacts that could be stored. Hence, the Datalink 150 could store 150 contacts. The other menu options were the same for each model. In addition to storing contacts, you could synchronize appointments and to-do lists. It had five daily alarms with 10 sounds to choose from.

There were 12 apps available, including a stopwatch and a scorekeeper for golfing. An attractive feature for collectors was the fact that the Timex Datalink watches were certified for space travel by NASA. A few astronauts mentioned the watch in their logbooks while on missions in space.

Why do others claim the Ruputer as the first smartwatch? In keeping with the growth and change in technology, four years made a big difference. Seiko’s interface on the Ruputer was much more advanced. This is because the Datalink used a dot matrix, or two-dimensional pattern array to represent characters. The time and date part featured two main rows of a seven-segment display. The lower part was a dot matrix display with scrolling capabilities and showed the day of the week and the time zone.

In contrast, the Ruputer was the first to feature a graphical interface and a 102 x 64 pixel LCD screen. Iconography and navigation models resembled today’s mobile IU. Additionally, the Datalink software could only be used with a 32-bit Windows PC. Still, Timex and Microsoft helped pave the way for the modern-day smartwatch. The Datalink watches were called PIMs (personal information managers). Bill Gates, who owned one (of course) demonstrated the watch’s capabilities on TV.

Modern Day Smartwatches

Both the Seiko Ruputer and the Timex Datalink were no doubt a part of pioneering technology, setting the precedent for modern-day smartwatches with their plethora of apps and capabilities. But because the user experience was so awkward and the battery life so short, the Rupert failed on the commercial market. And Although Timex continued to make improvements over the years, the Datalink made it to the 2006 list of PC World’s “25 Worst Tech Products of All Time” list.

After the advent of the LCD touchscreen, Timex disabled the software making the data part obsolete. Today, you may find these early “smartwatches” on eBay. Seiko doesn’t currently offer a modern smartwatch except for the Seiko Wena wrist pro smartwatch only available in Japan at this time. Timex has a wonderful line of smartwatches and wearable tech.

Issues like size and battery life are still problems with contemporary smartwatches, thanks to high-resolution displays. After five generations, Apple developed the always-on screen. (Ironically, the Timex Datalink watches had a battery life of three years in full mode).

In conclusion, it seems that once manufacturers stopped trying to shrink logbooks and address books to wrist size, the smartwatch could evolve to find its own purpose. Today, smartwatches are mainly fitness devices and such that work along with a smartwatch to use as a second screen.

But like time, technology marches on generation after generation.